On February 26th, we admitted the first baby of the season, a 2-week-old Great Horned owlet! Amazingly, he did not sustain any injuries after falling from his nest, but at this age, he depends on his parents for warmth, protection, and food.

Like all wild animals, the best option for baby raptors is to be reunited and raised by their parents. Unfortunately, the attempts to reunite Patient #26057 with his parents were unsuccessful, and an intervention became necessary. Luckily, our experienced and licensed rehabilitators will raise him until he’s ready for release!

A major consideration when rehabilitating babies is preventing them from imprinting on humans. Imprinting is a critical development stage where babies rapidly learn behaviors needed to survive. In the wild, babies imprint on their parents, but a baby raised in human care risks not learning the behaviors needed to survive after release. Some of the ways we prevent imprinting include:

- Grouping babies of the same species to learn from each other or giving them a mirror to look at themselves

- Minimizing all contact when caring for baby birds

- Using specialized puppets when delivering food to help them recognize their species

- Wearing a special camouflage uniform to conceal the human form, hiding our hands, body, and face

- Minimizing human-related sights and sounds; we never want them to associate our voices with food delivery so we never talk to them or talk in their presence

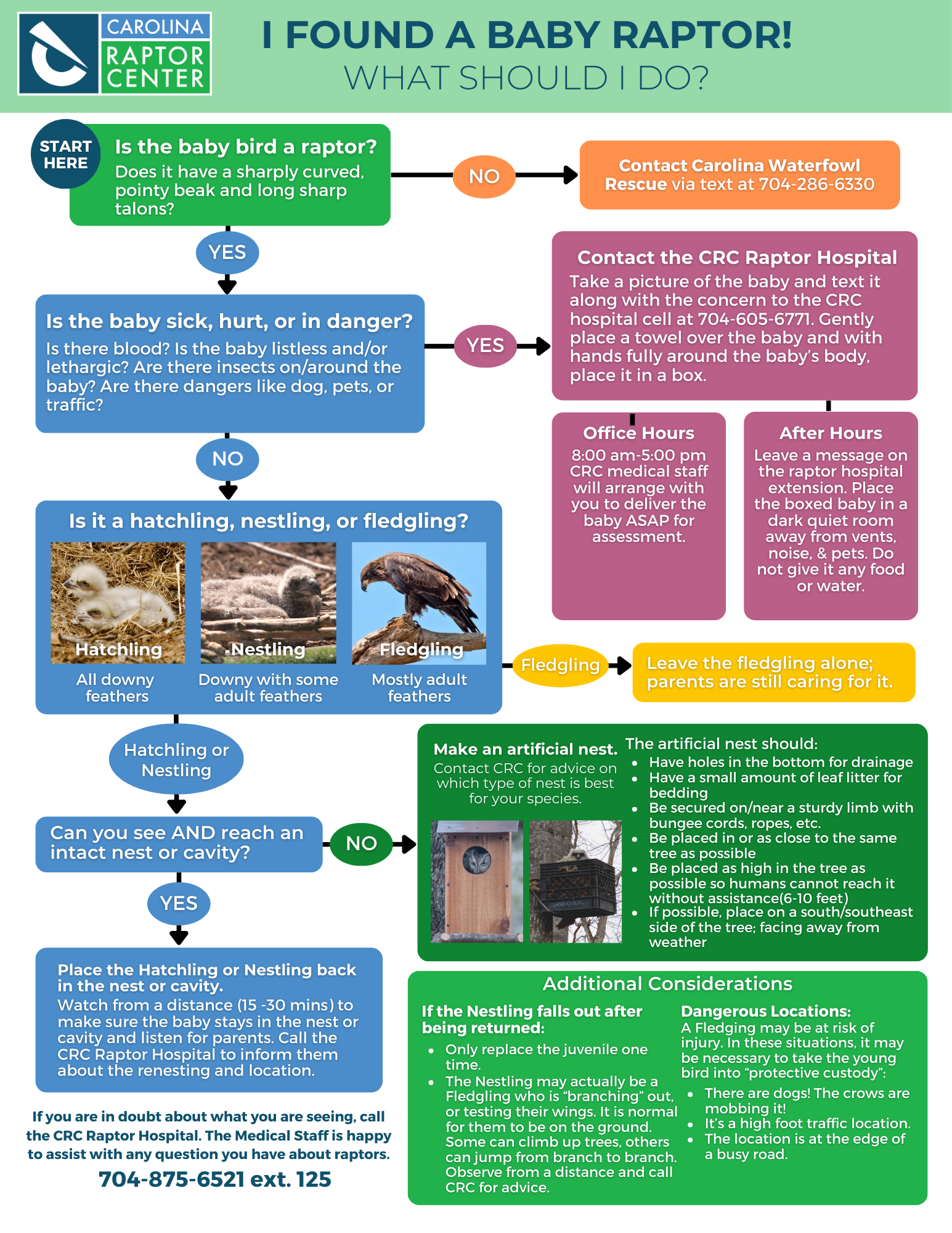

You can help baby birds succeed! The biggest mistake that caring people make is assuming that fledglings on the ground need help. Fledgling birds typically spend a week on the ground as they develop skills to fly. Follow this chart to help determine if a baby needs help.

Never attempt to raise a wild animal if you are not trained and licensed to do so. Caring for injured and orphaned wild animals requires special training, food, tools, and facilities, and the very best thing you can do for these animals is to get them to the closest permitted rehabilitator as soon as possible.

More Success Stories:

Cooper’s Hawk Struck By a Car

A Sticky Situation: Rescuing a Barred Owl from a Glue Trap

Rescued Barred Owl Nestling on the Road to Recovery

First Baby Owls of the Year

Saving a Scavenger: Treating a Turkey Vulture for Lead Poisoning

Rare Raptor Rescue: Caring for a Merlin at Our Raptor Hospital

How Bird Banding Helps Advance Raptor Rehabilitation and Conservation